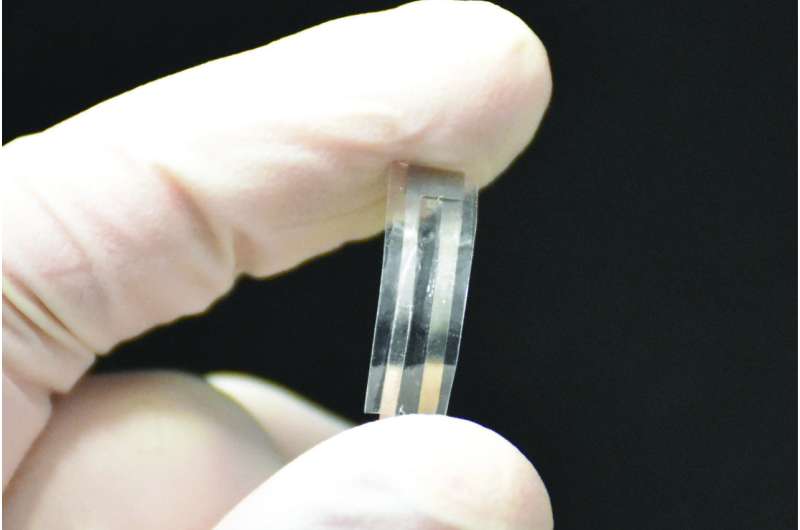

This biodegradable piezoelectric pressure sensor developed by the Nguyen Research Group at UConn could be used by doctors to monitor chronic lung disease, brain swelling, and other medical conditions before dissolving safely in a patient’s body. Credit: Thanh Duc Nguyen

UConn engineers have created a biodegradable pressure sensor that could help doctors monitor chronic lung disease, swelling of the brain, and other medical conditions before dissolving harmlessly in a patient's body.

The UConn research is featured in the current online issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The small, flexible sensor is made of medically safe materials already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in surgical sutures, bone grafts, and medical implants. It is designed to replace existing implantable pressure sensors that have potentially toxic components.

Those sensors must be removed after use, subjecting patients to an additional invasive procedure, extending their recovery time, and increasing the risk of infection.

Because the UConn sensor emits a small electrical charge when pressure is applied against it, the device also could be used to provide electrical stimulation for tissue regeneration, researchers say. Other potential applications include monitoring patients with glaucoma, heart disease, and bladder cancer.

"We are very excited because this is the first time these biocompatible materials have been used in this way," says Thanh Duc Nguyen, the paper's senior author and an assistant professor of mechanical and biomedical engineering in the Institute of Regenerative Engineering at UConn Health and the Institute of Materials Science at the Storrs campus.

"Medical sensors are often implanted directly into soft tissues and organs," Nguyen notes. "Taking them out can cause additional damage. We knew that if we could develop a sensor that didn't require surgery to take it out, that would be really significant."

A prototype sensor made by the lab consisted of a thin polymer film five millimeters long, five millimeters wide, and 200 micrometers thick. The sensor was implanted in the abdomen of a mouse in order to monitor the mouse's respiratory rate. It emitted reliable readings of contractions in the mouse's diaphragm for four days before breaking down into its individual organic components.

To make sure the sensor was also medically safe, the researchers implanted it in the back of a mouse and then watched for a response from the mouse's immune system. The results showed only minor inflammation after the sensor was inserted, and the surrounding tissue returned to normal after four weeks.

One of the project's biggest challenges was getting the biodegradable material to produce an electrical charge when it was subjected to pressure or squeezed, a process known as the piezoelectric effect. In its usual state, the medically safe polymer used for the sensor – a product known as Poly(L-lactide) or PLLA – is neutral and doesn't emit an electrical charge under pressure.

Eli Curry, a graduate student in Nguyen's lab and the paper's lead author, provided the project's key breakthrough when he successfully transformed the PLLA into a piezoelectric material by carefully heating it, stretching it, and cutting it at just the right angle so that its internal molecular structure was altered and it adopted piezoelectric properties. Curry then connected the sensor to electronic circuits so the material's force-sensing capabilities could be tested.

When put together, the UConn sensor is made of two layers of piezoelectric PLLA film sandwiched between tiny molybdenum electrodes and then encapsulated with layers of polylactic acid or PLA, a biodegradable product commonly used for bone screws and tissue scaffolds. Molybdenum is used for cardiovascular stents and hip implants.

The piezoelectric PLLA film emits a small electrical charge when even the most minute pressure is applied against it. Those small electrical signals can be captured and transmitted to another device for review by a doctor.

As part of their proof of concept test for the new sensor, the research team hardwired an implanted sensor to a signal amplifier placed outside of a mouse's body. The amplifier then transmitted the enhanced electrical signals to an oscilloscope where the sensor's readings could be easily viewed.

The sensor's readings during testing were equal to those of existing commercial devices and just as reliable, the researchers say. The new sensor is capable of capturing a wide range of physiological pressures, such as those found in the brain, behind the eye, and in the abdomen.

The sensor's sensitivity can be adjusted by changing the number of layers of PLLA used and other factors.

Nguyen's group is investigating ways to extend the sensor's functional lifetime. The lab's ultimate goal is to develop a sensor system that is completely biodegradable within the human body.

But until then, the new sensor can be used in its current form to help patients avoid invasive removal surgery, the researchers say.

"There are many applications for this sensor," says Nguyen. "Let's say the sensor is implanted in the brain. We can use biodegradable wires and put the accompanying non-degradable electronics far away from the delicate brain tissue, such as under the skin behind the ear, similar to a cochlear implant. Then it would just require a minor treatment to remove the electronics without worrying about the sensor being in direct contact with soft brain tissue."

More information: Eli J. Curry el al., "Biodegradable Piezoelectric Force Sensor," PNAS (2018). www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1710874115

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Provided by University of Connecticut